Ocean Drilling

Probing the Seafloor

Oceanographers had been able to collect sediment and rock samples from the ocean bottom ever since the Challenger Expedition. But they did not have the technology to enable them to probe very far beneath the seafloor.

In 1968, an international group of oceanographic institutions and the U.S. National Science Foundation created a program of ocean drilling. Its initial goal was to test Tuzo Wilson's hypothesis of plate tectonics.

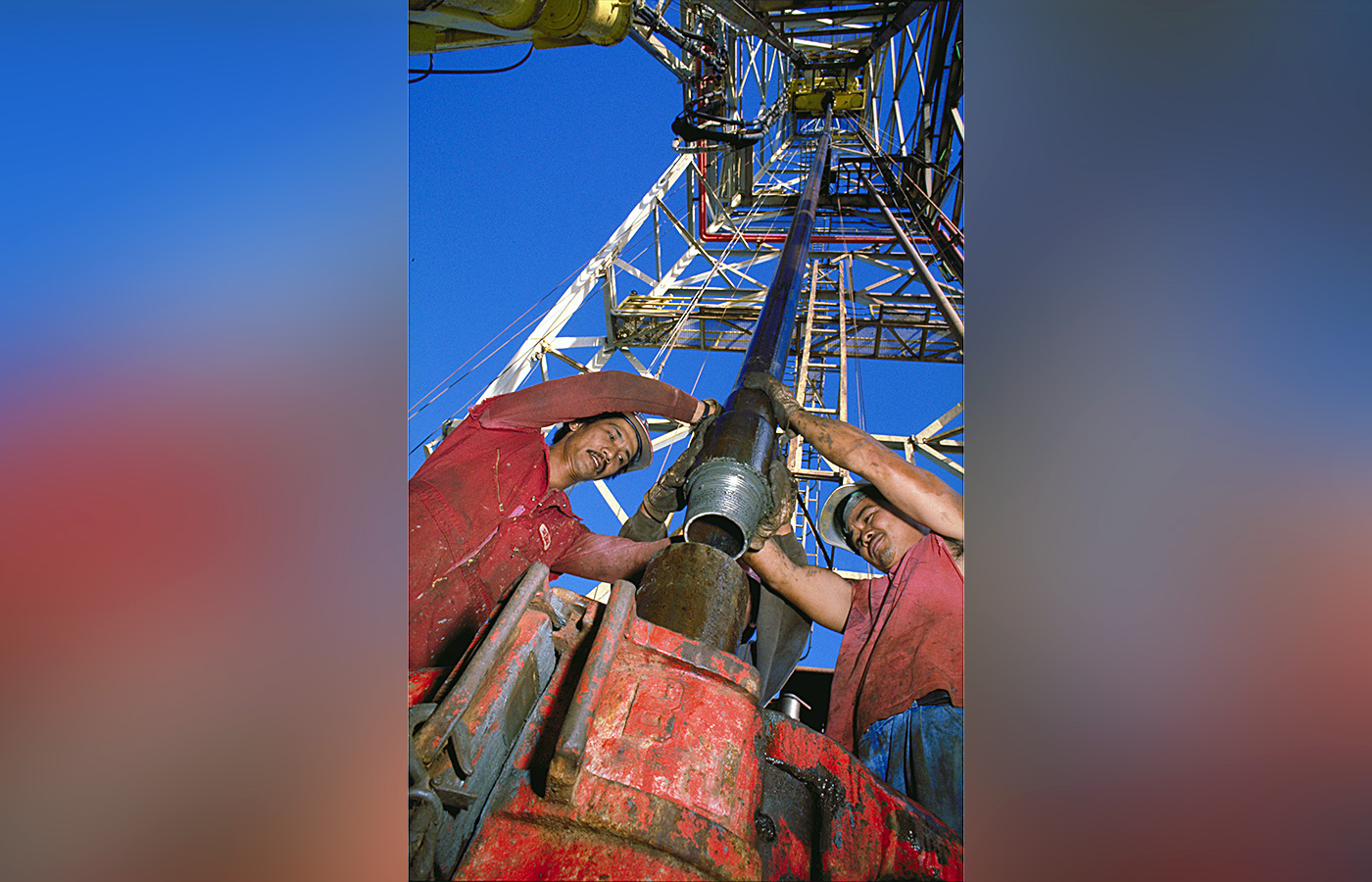

For 25 years, the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) operated the Glomar Challenger, a research ship 400 feet (122 meters) in length that was equipped with a drilling platform and scientific laboratories. From this platform, a string of pipes descended through water 20,000 feet (about 6,000 meters) deep into the ocean bottom. At the end of the pipes was a drill that cut into the seafloor. The system collected long, thin cylinders (meters long and centimeters wide) of sediment and rock from beneath the seafloor, called cores.

The cores provided evidence to confirm seafloor spreading and plate tectonics, but they also revealed much more. The long sections of sediments that accumulated layer by layer on the seafloor also provided a record of how the Earth's climate has changed during its history. The subseafloor sediments and rock also contained a treasure trove of clues that reveal the Earth's structure and evolution. Many of these clues cannot be found in rocks on land, because they are eroded away. But they are well-preserved below the seafloor.

The DSDP was so successful that a new international Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) was created in 1985. Ocean floor drilling continues today with a larger and more technologically advanced ship, the JOIDES Resolution. This 469-foot (143-meter) ship can drill in water that is 27,018 feet (8,234 meters) deep! It can dangle 30,030 feet (9,150 meters) of drill pipe through the hole in the center of the ship (called the "moon pool"). In addition, it has 10 laboratories where scientists can analyze the cores during cruises that typically last two months.

On drill ships, the sediment and rock cores are brought up from the bottom through the inside of the drill pipe in 30 feet long (9.5 meter) sections. Once on the deck of the ship, they are split in half. One half is studied in the ship's laboratories. The other is stored in special repositories, often called core libraries. There are three such libraries in the United States, on the East, West and Gulf coasts, and one in Bremen, Germany. Scientists from all over the world can come to these libraries and examine cores from all over the oceans-much the way you might go to a library to find a book. These core repositories will be a very valuable scientific resource for many years to come.