|

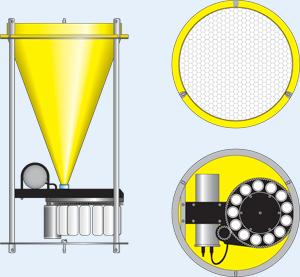

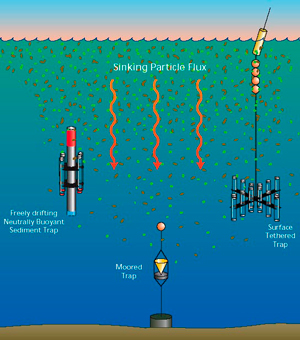

Sediment TrapsSediment traps are containers that scientists place in the water to collect particles falling toward the sea floor. The traps collect tiny grains of sediment or larger clumps of debris called marine snow made up of organic matter, dead plankton, tiny shells, dust, and minerals. The basic sediment trap consists of a broad funnel with a collecting jar. The funnel opening covers a standard area (such as 0.25 square meter [2.7 square feet]). Anything falling into the funnel is directed into the collecting jar at the bottom. Deep-water traps, which often stay in the water for up to a year, have several jars on a motorized, circular tray. After a set period of time, or if other instruments on the trap detect a change in water conditions, a new collecting jar rotates into place and the old jar seals. Analyzing the samples helps scientists understand how fast nutrients and trace elements like carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, calcium, silicon and uranium move from the shallow ocean to the deep ocean. These materials are also what almost all deep-sea life uses for food (since plants can’t grow in the dark). Other researchers analyze the trace elements in the shells for clues about ocean circulation thousands of years ago. Before sediment traps, scientists assumed that nutrients and the tiny bodies of plankton would sink very slowly, taking centuries or millennia to finally reach the sea floor. During the long descent, they thought, much of the material would dissolve into the water or be consumed by sea life and never reach the bottom. Just how deep-sea life could survive with so few nutrients arriving became a puzzle. Sediment traps showed that much larger particles (to 12 mm [0.5 inch] long) were reaching the bottom than scientists expected. This marine snow (so-called because of its light color and fluffy texture) sinks as fast as 200 meters (656 feet) per day and can reach the bottom in just a few weeks. At that speed, changing surface conditions, like a summer bloom of phytoplankton, can affect the sea floor relatively quickly in the form of a blizzard of marine snow. Sediment traps have to remain vertical in the water to work properly. Traps deployed in strong currents must continuously record their tilt angle so scientists can tell whether the samples have been compromised. Sediment traps are usually mounted on a cable that is anchored to the sea floor and held up by a subsurface or a surface buoy. The traps are bolted onto the cable at specific depths, where they remain for up to a year before a research vessel returns to collect the samples. When a ship returns to retrieve the trap, the crew activates a remote-controlled device called an acoustic release. The release separates the line between the trap and its anchor, and the trap floats to the surface with its samples.

|

Mailing List | Feedback | Glossary | For Teachers | About Us | Contact

© 2010 Dive and Discover™. Dive and Discover™ is a registered trademark of Woods

Hole Oceanographic Institution