Alvin Upgrade

Click to enlarge Click to enlarge

A preliminary view of the upgraded submersible, when the new personnel sphere and other additions are in place. (Illustrated by Megan Carroll, WHOI)

Click to enlarge Click to enlarge

One of the forged hemispheres cools. Material from the hemisphere's interior and exterior was later removed to reduce its thickness to 3 inches. (Photo courtesy of the Advanced Imaging & Visualization Laboratory, WHOI)

Click to enlarge Click to enlarge

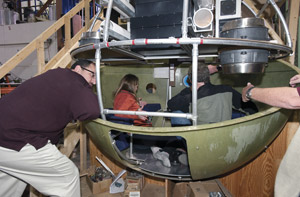

Scientists test a mock-up of the new Alvin sphere constructed by engineers at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. They offered feedback on ways to make the sphere more comfortable and effective. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, WHOI)

The new Alvin will have more viewports, giving better visibility from inside the sub. Designers modeled the pilot’s and passengers’ views while gathering a sediment core. (Courtesy of Susan Humphris, WHOI)

Upgrading Alvin

Three times geologist Adam Soule has climbed inside the deep-diving submersible Alvin and headed to the seafloor. Geochemist Susan Humphris stopped counting after 30 dives. Dan Fornari, who studies deep-sea volcanoes, has descended more than 100 times.

Yet for all of them, the deepest seafloor depths have remained out of reach. Alvin is not designed to withstand pressures beyond a depth of 4,500 meters (2.8 miles). “Right now, Alvin allows us to see 63 percent of the ocean,” Fornari said. “We want to see 98 percent.” That would require descending to 6,500 meters, or more than 4 miles.

In the late 1990s, ocean scientists began aiming for that goal with plans to replace Alvin, which made its first dive in 1964 and has since carried more than 9,000 passengers and made more than 4,600 dives. They proposed a next-generation vehicle that could go deeper, spend more time on the bottom, provide more interior room, and give scientists a more expansive view outside the sub.

But as costs rose, particularly for the metal titanium, which is used to make the sub’s personnel sphere, it became apparent that a more cost-effective plan would be to simply upgrade the existing vehicle. So now, engineers will build several new, key components and integrate them into the existing Alvin starting in early 2011.

During Stage 1, engineers will modify Alvin’s frame and add a larger, stronger sphere with more viewports. As funding becomes available, Stage 2 calls for other systems to be modified to increase the sub’s diving range to 6,500 meters. By that time, new batteries—most likely involving lithium-based chemistry—should be available that will increase the sub’s energy capacity to permit longer and deeper dives.

The new, 3-inch thick sphere is among the biggest technical challenges of the upgrade. To build it, engineers needed more than 34,000 pounds of titanium, about the weight of a large school bus. Two huge, barrel-shaped ingots were fabricated by a mill in Morgantown, Pennsylvania, and reshaped into two giant hemispheres in Cudahy, Wisconsin. These were then shipped to Los Angeles, where workers joined the two hemispheres using a special welding technique. They also cut inserts for the hatch, electrical and fiber-optic connections, and five viewports. Right now, Alvin has three viewports, one in front and one on each side. With more viewports, pilots will have better visibility to drive the sub and use the manipulator arms. Scientists will also be able to help guide the pilot better and make better observations of the seafloor.

In the end, the sphere needs be nearly flawless—free of any deformities that could weaken its structure and potentially cause it to crumple under pressure—and as perfectly spherical as possible. Deep-sea explorers often ride in spherical crew compartments. Because a sphere has no corners, its geometry distributes external forces evenly over its entire structure, making it the strongest possible shape. And at depths of 6,500 meters, pressure will reach nearly 5 tons per square inch.

Re-designing Alvin from the Inside Out

For more than four decades, scientists have sacrificed comfort in order to visit the bottom of the ocean.

On a typical dive, a pilot and two scientists climb through a narrow hatch into an equipment-filled, 6-foot-diameter sphere. Once sealed inside, they have no room to stand up, no seats, and no bathroom. For up to eight hours, they sit on thin pads on the floor and peer out windows, or viewports, the size of teacup saucers. The pilot drives while perched on a small metal box.

“It sort of equates to sitting in a phone booth with two of your closest friends, all day long,” said Patrick Hickey, Alvin operations manager at WHOI, who has logged 636 dives as a pilot.

The space is tight for a good reason. The sub’s current, 2-inch thick personnel sphere is packed with equipment and machinery. It also maintains sea-level pressure inside for its occupants, while resisting mounting pressure from outside as the sub dives deeper.

Before redesigning the interior of the sphere, engineers first considered the size and weight of every item that must fit inside the submersible on each dive—a list that includes about 300 items. Every switch, shelf, and emergency flashlight—even the pilot’s small seat—must be weighed to ensure that Alvin has enough buoyancy to keep the submersible upright and stable during a dive. The remaining space goes to the pilot, the scientists, and the small bags of items that they bring with them (typically a snack, notepads or other recording devices, and warm clothing).

As to how they will position themselves, scientists will soon have more options. The new locations of the viewports required seating changes, which gave engineers an opportunity to build in some additional comfort, but not much. Now, passengers often sit on the floor, with their heads on opposite sides of the sphere and their legs poking into the center, trying not to kick each other or the pilot’s metal box seat. To get people off the floor, engineers have proposed adjustable benches that allow passengers the choice of kneeling, sitting, or lying flat.

With such an expensive and carefully crafted investment, why not make the new sphere really snazzy by adding reclining leather seats? How about a few cozy cashmere blankets and an Italian coffee maker to help fight the chill of temperatures that average 55° to 65°F inside the sphere?

Weight limits prohibit too many frills. Safety considerations also add constraints. But lack of comfort is part of the experience. Sharing a ride in Alvin bonds people, in the same way that people sometimes feel a shared experience after making a long car trip. “People know that they have endured one of the more uncomfortable rides on Earth to be a part of a really special group,” German said.

This article was adapted from reports in Oceanus magazine. Read more about Alvin’s interior and exterior re-design, as well as what it’s like to dive in the sub by downloading a PDF of our Alvin brochure.

[Back

to top]

|

Keeping

the “Big O” Out of Alvin

Keeping

the “Big O” Out of Alvin