|

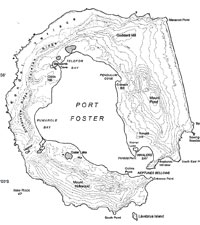

By Kate Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution   Download a map (pdf) of Deception Island. (Map courtesy of Eric Hutt, Raytheon Polar Services Company, R/V LAURENCE M. GOULD) Deception Island has fire and ice in its history, and in the present day. Mountainous, half covered by glaciers and mostly covered with black volcanic ash, Deception is an active volcano. The island is a “submerged caldera,” a circle of craggy hills around an almost-enclosed seawater lagoon, known as Port Foster. Its horseshoe shape formed when a volcanic eruption 10,000 years ago that blew off the top of the mountain and allowed seawater to flood the center, or caldera. This volcano is quiet, but not dead. The island is classified as a “restless caldera with significant volcanic risk,” that could erupt at any time. Eruptions in 1968 and 1970 forced a British scientific research station to close, sending mud and ash through it and the nearby abandoned whaling station. Geologists continuously monitor the island for seismic activity. For the remaining two research stations, of Spain and Argentina, and for visiting researchers, a detailed evacuation plan describes escape routes for another eruption. Deception Island is now managed as part of the Antarctic treaty, making it a protected area with restricted human visits and impacts. But its history also records some of the human over-use of the Antarctic. Human activity there began in about 1820, with sealing. But in the early 1900s, when seals were nearly hunted to extinction, Antarctic seafarers turned to whaling. In the austral summer of 1906-7, a Norwegian Captain, Adolfus Andresen, began whaling at Deception. Whalers Bay—sheltered, shallow, with a wide beach—was an ideal location to establish the Hektor whaling station, for factory ships that processed whale blubber into whale oil, a valuable commodity for lubrication, lighting, and other purposes in the early twentieth century. The whalers established residences, a kitchen, a hospital, and a small cemetery. They kept pigs for food, and brought slain whales in the cove to process. In 1931 the Hektor station closed, as the price of whale oil fell and it was no longer profitable to hunt whales in the Antarctic. British researchers then used the same site for their scientific station. The ruins of this station are the most complete remains of whaling history in the Antarctic, and governments have agreed to let the remains stand, undisturbed, to be seen and understood as part of maritime history—and as a witness to the power of volcanic activity. A visit here leaves an equally powerful impression, and Deception Island is the most-visited site in the Antarctic. Several nations conduct scientific research here, including the U. S., Spain, Britain, Argentina, and Chile, and many cruise liners and tours regularly stop here. Recently, governments and tour companies have cooperated to limit the numbers of people allowed to visit, and each ship must plan visits in advance, to lessen their impact on the island and its life. Deception Island is part of the line of islands called the South Shetland Islands, lying northwest of the Antarctic Peninsula. It is an extremely important botanical area: in spite of its forbidding volcanic rocks, there are some plants on the island, many of them rare. Some 18 species are unique to Deception. Many parts of the island are ecological study sites where people are forbidden. Seals, seabirds, and penguins live on Deception Island and in its enclosed central lagoon. On the outside perimeter of the island’s circle, exposed to the sea, is the world’s largest colony of chinstrap penguins—nearly 400,000 birds live there, but it is strictly off limits to visitors. Other penguins stop by, or rest there at times. Other birds, including skuas, sea gulls, petrels, and cormorants can be seen from the ‘inner coast’—the inside ring of cliffs and beaches around the central lagoon. Seals of several kinds, including Weddell, fur, crabeater, leopard, and southern elephant seals “haul out,” or clamber ashore, to rest for long periods on the rocks and beaches of Deception Island. Though seals arc out of the water in apparent play, and spar with each other on land, no seals breed here. In this unique place, you may see a seal, a penguin, volcanic rock, a glacier, and ash-filled buildings, and rusted whale oil tanks in the same view—a reminder that humans have a huge impact on the natural world, and that we are also part of that world, and no match for a volcano.

|

||

Mailing List | Feedback | Glossary | For Teachers | About Us | Contact

© 2010 Dive and Discover™. Dive and Discover™ is a registered trademark of Woods

Hole Oceanographic Institution