|

Our Mission Dive and Discover's Expedition 10 will explore one of the coldest, most remote places on our planet—the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica. Using scuba diving and other sampling techniques, scientists will study the mysteries of salps In the Austral But, there is another major player in the Southern Ocean food chain—the salps. They are often overlooked, but are sometimes so numerous they seem to take the place of krill populations. Salps are gelatinous, tube-shaped animals that live in all oceans. Like krill, salps eat phytoplankton, so they often compete for the same food. Salps feed by pumping water through their hollow bodies and sieving phytoplankton out with an internal filter net.

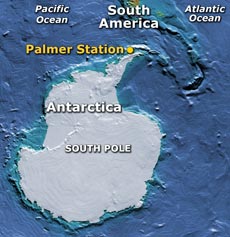

How the Isthmus of Panama Put Ice in the Arctic On the Seafloor, Different Species Thrive in Different Regions Funding Agency: In the last thirty years, scientists have observed an overall decrease in the numbers of krill and an increase in numbers of salps in the waters surrounding Antarctica. The shift in abundances of these animals may be related to changes in the amount of sea ice around Antarctica, which is in turn affected by global climate. More ice may favor the krill, because they can feed on algae growing under the ice. Less ice may favor salps, which swim and feed in open water. To discover whether this is true, we need more information about the behavior and life cycle of both salps and krill. Scientists know much more about Antarctic krill than about Antarctic salps, mainly because krill are easier to catch and study than the fragile, jelly-like salps. On Expedition 10, scientists from several universities and institutions will sail on the R/V Laurence M. Gould from the tip of South America to the waters around the Antarctic Peninsula to observe and sample Antarctic salp populations. This research is funded by the National Science Foundation. Salps are too fragile to catch alive in nets, so researchers will collect them by scuba diving. Plankton nets towed behind the ship and special underwater video cameras will help researchers determine and map the distribution and abundance of the salp population. Back on board the ship, biologists will keep salps in cold seawater in specially designed tanks to measure how much phytoplankton they eat in a day, and how much they grow. Some of the scientists will study how the salps’ filter feeding mechanism works, and which phytoplankton cells are most nutritious for them. Researchers will also measure salp metabolic rates to see how much food is required for the population to thrive. In addition to mapping the distribution and abundance of salp populations, scientists will also measure their vertical migration through the water column—a pattern of behavior that causes them to swim up to the surface at night and back to deep water during the day. The causes of this daily migration by salps are still a mystery. Other research projects will also be a part of Expedition 10. They include a study of whale genetics, based on samples of old whale bones left at an abandoned whaling station on Deception Island, and biological studies on feeding and growth by a different gelatinous animal—a ctenophore, or “comb-jelly”—that preys on young krill. Join our team as we dive below cold Antarctic waters and discover the mysteries of salps, surrounded by the stunning beauty of the frozen southern continent.

|

Mailing List | Feedback | Glossary | For Teachers | About Us | Contact

© 2010 Dive and Discover™. Dive and Discover™ is a registered trademark of Woods

Hole Oceanographic Institution